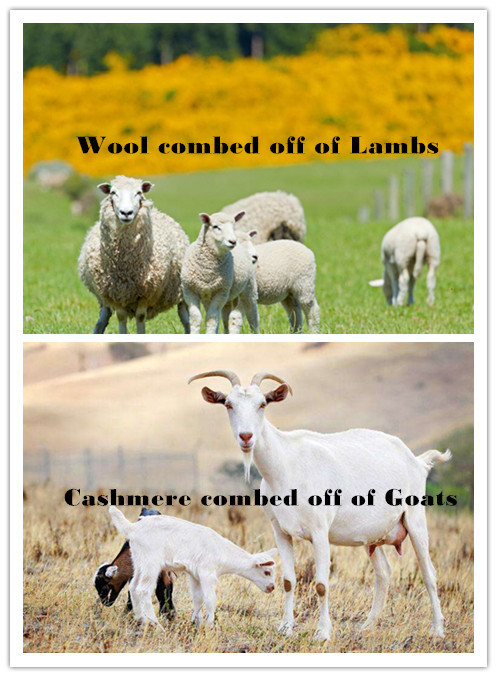

Cashmere comes from the soft undercoat of goats bred to produce the wool. It takes more than two goats to make a single two-ply sweater. The fibers of the warming undercoat must be separated from a coarser protective top coat during the spring molting season, a labor-intensive process that typically involves combing and sorting the hair by hand. These factors contribute to the relatively low global production rate of cashmere.

High-quality cashmere can be up to eight times warmer than sheep’s wooldespite its light weight. But not all cashmere is equally luxe: The texture, color, and length of the fibers all affect manufacturing and pricing. Naturally, whiter cashmere fibers require less dye, diminishing the damage that coloring causes to its natural softness. Quality also depends on the region in which the wool is collected. In Inner Mongolia, for instance, the winters are harsh and the goats have a more meager diet, which produces the finer hair seen in the highest quality garments. Still, even the best raw material can be compromised by a sub-par finishing process. The fineness of a cashmere item comes down to that process, as the spinning and weaving of the fabric affects the look, feel, and touch of the final product.